The Stories We Tell: Land Acknowledgements & Indigenous Sovereignty

We wear the threads of so many stories in our lives, often without examining their weave more closely.

The practice of land acknowledgements is a well-intended attempt by non-indigenous organizations to address a broken collective relationship with history, the erasure of genocide and colonization, and alienation from the land upon which human life depends. And, the most well-intended narrative interventions can still be bent to the will and need of domination and power-over.

Do land acknowledgements, as practiced, tell the story that our movements need? Do they open up new futures for indigenous sovereignty and movement solidarity? Or do they reinforce stories about justice and reparations being far out of reach? CSS looks to indigenous communities for leadership on the questions raised in this conversation, while also assuming an active and accountable role in our own storytelling.

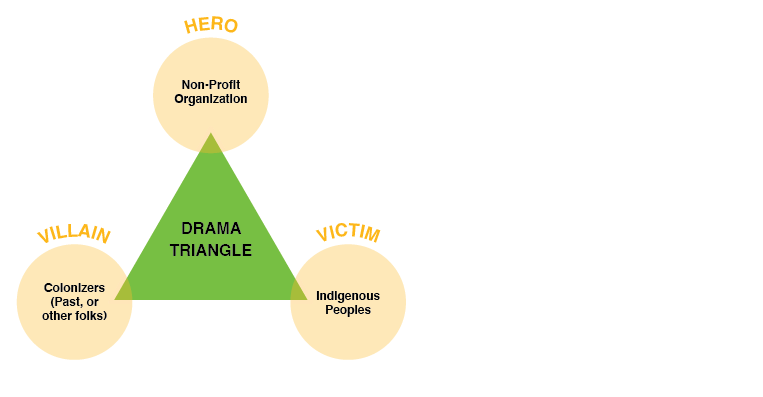

Let’s start with a written land acknowledgement that feels like a fair representation of how many are phrased. This one is from an academic institution — not linked here because the point of this exercise is not the critique of specific wordsmithing or a single institution. Let’s look at this brief statement as an example of the wider practice:

"We pause to acknowledge that this University sits on the land of the Ohlone and the Muwekma Ohlone people, who trace their ancestry through the Missions. We remember their connection to this region and give thanks for the opportunity to live, work, learn and pray on their traditional homeland. Let us take a moment of silence to pay respect to their Elders and to all Ohlone people past and present."

There are various Elements of Story on display here. Unpacking these elements helps one analyze how the story works, as currently written. Use the arrow buttons to scroll across:

Drama Triangle

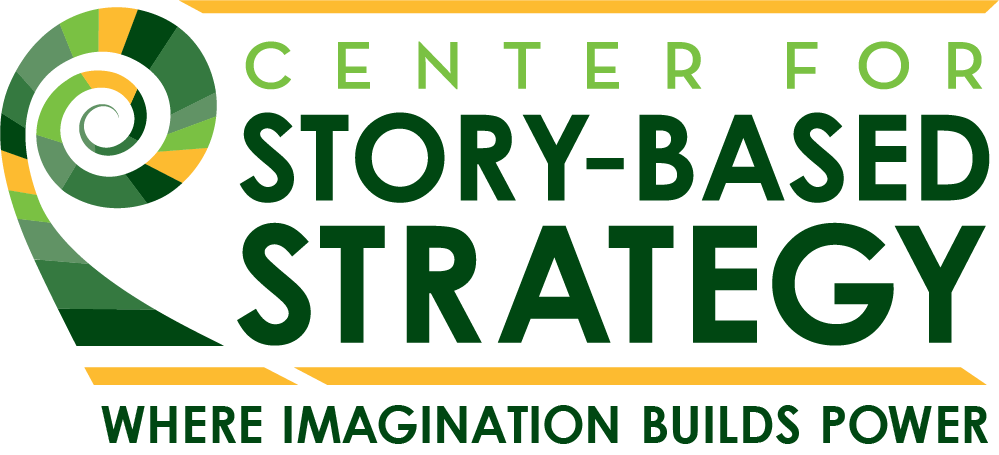

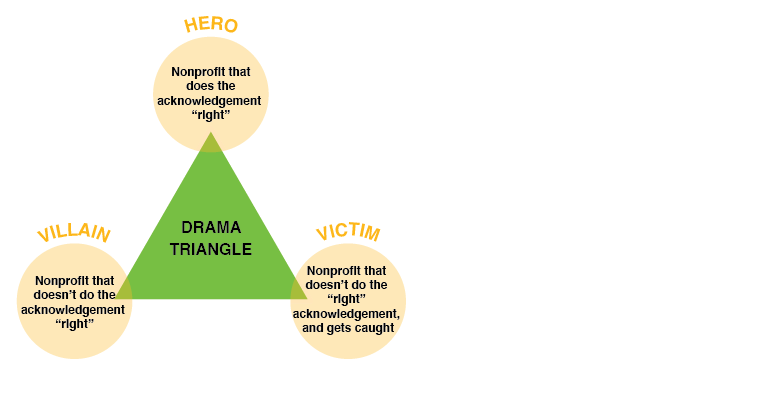

Next, Drama Triangle is a simple tool to help explore the structure of conflict in a story. Naming the hero, victim, and villain in one story, can help clarify similarities and differences with another. And when the current story is not to our liking, moving and re-casting characters in the drama triangle can help us experiment with new storytelling strategies.

Any story is fair game for drama triangle, and there’s no better place to start than stories we tell about ourselves.

Land acknowledgements happen in a particular context of shared culture and politics across many movement organizations, nonprofits, and other spaces. Often one of the unexamined assumptions in the stories we tell ourselves is that we, the storyteller, are the good ones, the heroes. Getting comfortable with the complexity of accountability, not always being heroes, considering assessments of our stories that demand corrective action — are all important outcomes of this sort of narrative reflection.

Taking Action

As we work to bring our organizational culture in line with our values, this exploration of land acknowledgement narratives helps clarify a few things for us:

Leaving our villains in history encourages North Americans to mourn the loss of diversity while ignoring the present power dynamics. You should be wary of telling stories that you aren’t in — this one is enticing because it moves non-Indigenous folks out of the story, and thus away from accountability.

We call them land acknowledgements, but our relationship with the land itself is often made invisible. We can avoid falling into passive progressive messaging by naming the land as a character in our stories, acknowledging active land struggles during acknowledgements, and donating to a local Land Tax.

Land acknowledgements are a tiny piece of the larger fight for indigenous sovereignty and turning us to right-relation with the natural world. Support People’s Orientation for a Regenerative Economy. Following the leadership of movement partners like Indigenous Environmental Network, we know there is no climate justice without indigenous sovereignty.